K. Autiö

The electric car was not born from Silicon Valley or Tesla’s mythos. It was born in the soot and clatter of the late nineteenth century. In Paris, inventor Gustave Trouvé rolled through the boulevards on an electric tricycle. In the American Midwest, William Morrison built a boxy electric carriage that could carry six passengers at a modest fourteen miles per hour. By the early twentieth century, companies with names like Columbia, Detroit Electric, and Baker Motor were manufacturing elegant vehicles with glass cabins, velvet seats, and battery ranges of fifty miles—a small miracle in a time of horse dung and coal dust. The electric car, for a brief moment, was civilization itself: modern, domestic, unthreatening. Women drove them. Doctors made their rounds in them. Thomas Edison drove one; so did Clara Ford, who preferred her whispering Detroit Electric to her husband’s new belligerent Model T.

And then, it vanished.

What killed the early electric car wasn’t the failure of imagination; it was the failure of infrastructure. Gasoline could be bottled, shipped, and pumped anywhere. Electricity could not. The gasoline engine, ugly and explosive as it was, was easy. Worse, when Charles Kettering invented the electric starter motor, the one thing that made gasoline cars unpleasant—the brutal crank—disappeared overnight. Ford’s assembly line made cheap gasoline-powered automobiles, and the oil barons made sure fuel was even cheaper. By 1920, the quiet hum of electric progress had been drowned out by the triumphant growl of combustion.

But technology, like memory, loops back on itself. Every time the world stumbles, we return to the ideas that never truly die. In the 1970s, amid oil shocks and ecological unease, a small company in Florida called Sebring-Vanguard resurrected the dream in the form of the CitiCar, a bright plastic wedge with golf-cart bones and a household plug. It was ugly, fragile, and deeply sincere. The world laughed, but the seed was replanted.

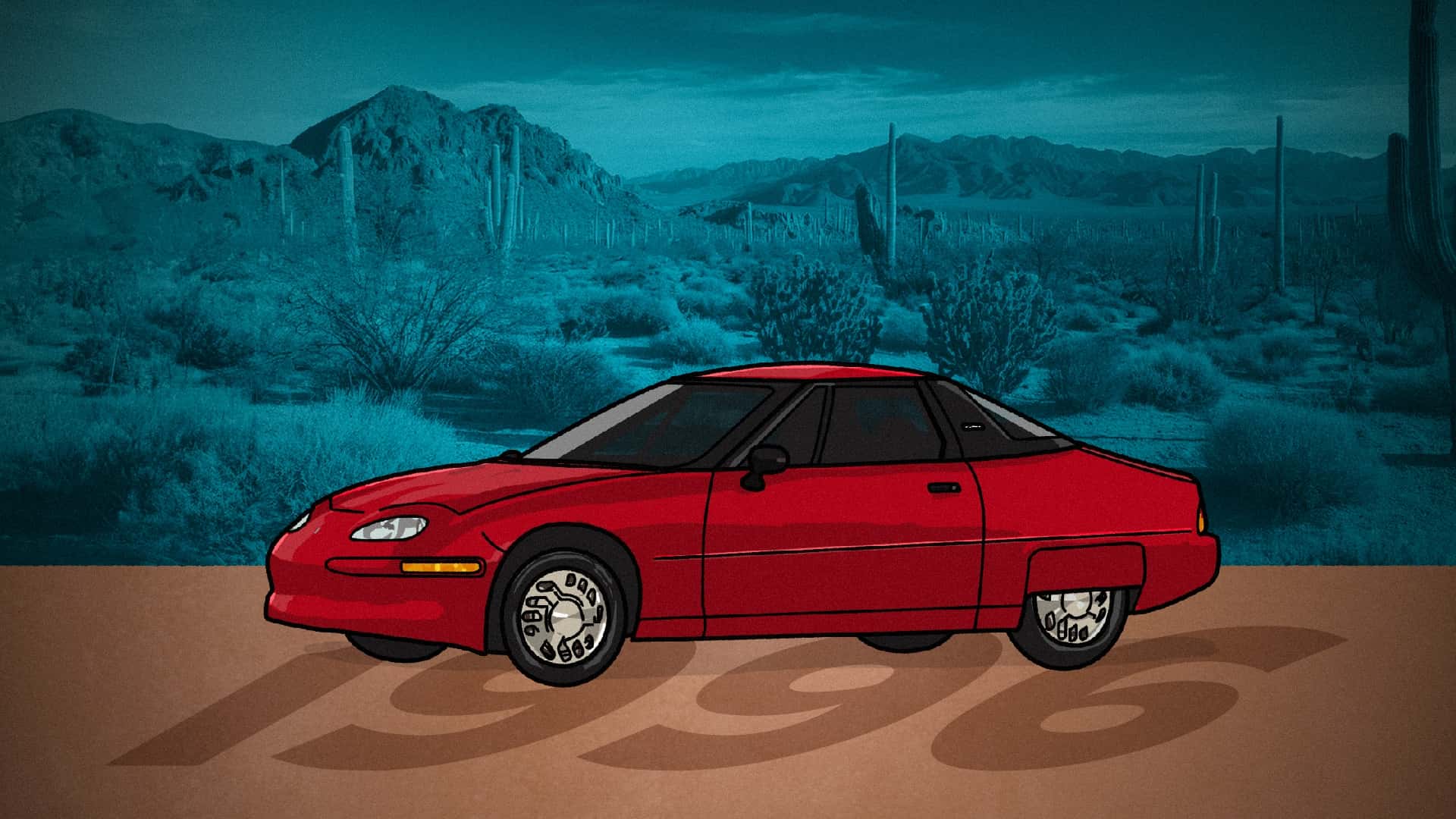

The pattern repeated in the 1990s when General Motors rolled out the EV1, a low-slung silver ghost that actually worked. Drivers adored it. It purred instead of roared. It should have been the turning point. But GM flinched. The company recalled the leased cars and fed them to the crusher, as if progress itself had made them nervous. Around the same time, Honda flirted with the EV Plus—quiet, efficient, weirdly charming—and then yanked it from the market like a secret it regretted telling. Ford toyed with electric conversions like the EVcort and the Ecostar, the latter powered by sodium-sulfur batteries that sometimes caught fire. Better to burn out than plug in, apparently. Each of these experiments was a brief, brilliant relapse into sanity, cut short by cowardice. How many times does the future have to show up before someone opens the door?

The present moment, the sleek, lithium-ion renaissance of the twenty-first century, is not invention but return. We are not discovering electric cars; we are remembering them. Each new battery is a palimpsest of forgotten prototypes and lost ambitions, every charging station a quiet apology for a century of exhaust. The future hums in familiar tones. It doesn’t sprint forward; it circles back, testing the circuit, tightening the coil, finding new charge in the old idea.

But for this latest return to endure, what we need most isn’t a better battery—it’s belief. We have to fall in love again with the idea that progress can be elegant, that clean technology can feel like triumph, not penance. The hardest part of any revolution isn’t the science; it’s the story. We have to believe the future deserves saving, and that this time, we’re brave enough to keep it. If enough people choose wonder over cynicism, faith over fatigue, the current will hold. The electric car won’t just be an object of redemption or guilt; it will be proof that recursion can lead somewhere new.

Recursive futurism is the shape of that faith: progress that remembers itself. It’s evolution that reclaims what it once discarded, a rhythm that repeats until it finally gets it right. The first electric cars were born from a desire for ease; the new ones are born from necessity. Either way, invention never travels in a straight line. It arcs, returns, and refines, each generation recharging the dream the last one abandoned.

Art, too, obeys this looping current. Every movement that declares itself new is, in truth, a return to form, to feeling, to the ghosts of unfinished ideas. The avant-garde borrows from the ancient; modernism reanimates myth; digital art resurrects the analog it once sought to erase. In this sense, artists are engineers of memory, coaxing lost futures into view. Recursive futurism isn’t just a theory of machines; it’s an aesthetic condition, a way of seeing the past as raw material for invention. When art remembers itself, it becomes prophecy again—proof that progress and beauty share the same circuit, endlessly returning, endlessly alive.

Links