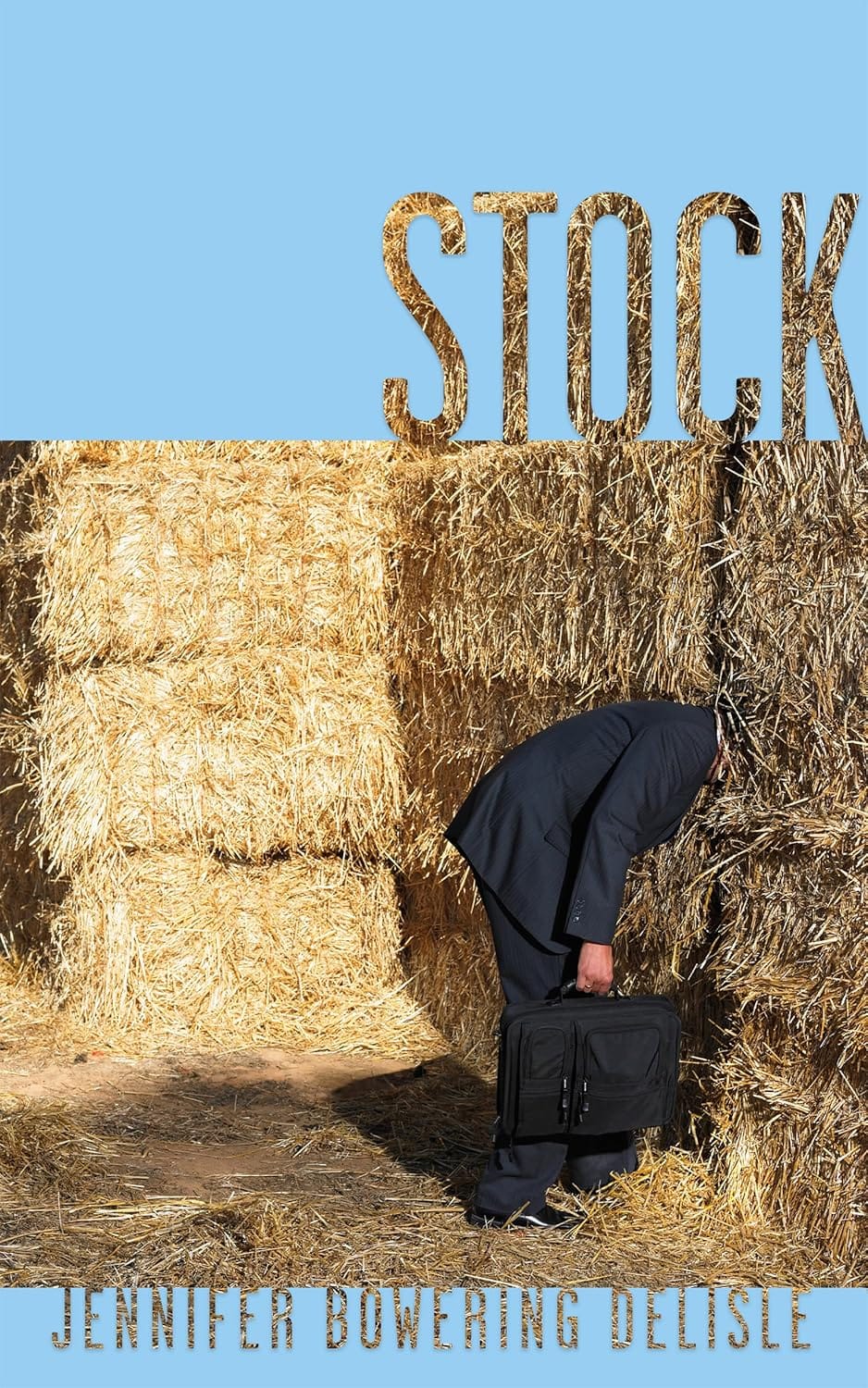

Stock by Jennifer Bowering Delisle

Jennifer Bowering Delisle’s conceit is simple and devastating. Each poem begins with stock-photo search terms—“MOTHER DAUGHTER SMILING HUGGING,” “LADY BOSS SMILES WITH ARMS FOLDED,” “7,888,365,123 ROYALTY-FREE EARTH IMAGES”—before unspooling into lyric or monologue. Delisle takes the dead language of the internet and animates it, like someone breathing into a mannequin.

What she’s done is structurally ingenious: using the detritus of digital culture as poetic material. She’s thinking hard about how women, mothers, and even the planet itself are consumed as images—flattened into searchable keywords. The project gestures toward the linguistic architectures of Lisa Robertson and the archival reclamations of M. NourbeSe Philip, though Delisle’s materials are digital rather than textual—pixels and code instead of paper and empire.

The emotional material—motherhood, grief, labour, ecological collapse—is all here, but it often arrives obliquely rather than head-on. The book is clear about feeling without always trying to make us feel it directly. Its strongest moments come when the structure loosens, when the conceit fades for a beat and something more human slips through. Those moments land precisely because they sit just outside the system she’s built. You sense Delisle knows this; the ending almost suggests that while critique has its limits, beauty still has a chance.

In HAPPY MOTHER AND CHILD SON IN THE KITCHEN BAKING COOKIES HAVING FUN, Sarah describes buying a Victorian memento mori photograph on eBay and initially believing the sitters were dead—“children with stiff dresses and painted eyelids.” Later she learns (or thinks) this was a myth: the sitters were alive, held still by iron clamps for the long exposure. The revelation turns elegy into self-reflexive critique. Sarah feels “both cheated and relieved,” recognizing her own need for the image to contain death. It’s a breathtaking pivot. The poem becomes both séance and simulation, collapsing the act of witnessing into the act of wanting to believe. In that moment, Delisle links the hidden mothers of early photography to the invisible women propping up digital culture now, each holding still long enough to make someone else’s image possible.

Sarah—the recurring voice who speaks from within and against the stock-photo captions—is one of Delisle’s sharpest inventions. Sarah, “who keeps her soap in wicker / who kneels before the front loader / caressing labour…,” is both construct and character: part algorithm, part archetype, a woman assembled from keywords and clichés. At her best, Sarah’s monologues are strange, witty, and wounded. At other moments, she risks becoming what she’s meant to critique—an idea of womanhood rather than a woman. Still, her presence is essential to the book’s feminism. She’s the test subject in an experiment about representation, proving that even the most overexposed image can still carry a trace of consciousness.

This is where the book deepens. Stock isn’t preaching empowerment; it’s mapping how even care and tenderness are colonized by representation. The mothers, the bosses, the models all carry the burden of being symbols first, beings second. Delisle doesn’t offer liberation so much as awareness—resistance without spectacle. After all the branded mothers and glass offices, she ends with the ultimate exploited image: the world itself. “If I am to be a body,” the Earth pleads, “why not a dragon?” It’s a perfect close—rage recast as myth, exhaustion sublimated into art.

Stock is a book of radiant surfaces that knows exactly how shallow they are. At times it’s a little too neat, too deliberate, but its intelligence is undeniable. When it lets go of irony and allows language to feel, it’s breathtaking. Delisle has written a mirror of our age—polished, recursive, and just cracked enough to show what’s real beneath.

Epilogue: The Last Human Image

Delisle couldn’t have known how quickly the world would catch up to her. The stock-photo archives she mines are already disappearing, replaced by frictionless AI images with no models, no labour, no hands behind the lens. Stock may be the last human interrogation of that aesthetic—the final portrait before faces dissolve into prompts and pixels.

When Earth says, “The mass of things you’ve made / is now greater than the mass / of all the living things,” the line lands like prophecy. It isn’t only ecological collapse she’s mourning; it’s the moment replication outnumbers the original. Delisle has written an obituary for stock photography—and maybe for us, too: the ghosts still teaching the machine how to smile.

Jennifer Bowering Delisle is the author of Micrographia, Deriving, and The Bosun Chair. She teaches creative writing at the University of Alberta and serves on the board of NeWest Press. She lives in Edmonton / Amiskwacîwâskahikan on Treaty 6 territory with her family.

Publisher: Coach House Books (September 9, 2025)

Format: Paperback | 96 pages

ISBN: 1552455106

Subscribe to my newsletter to get the latest updates and news